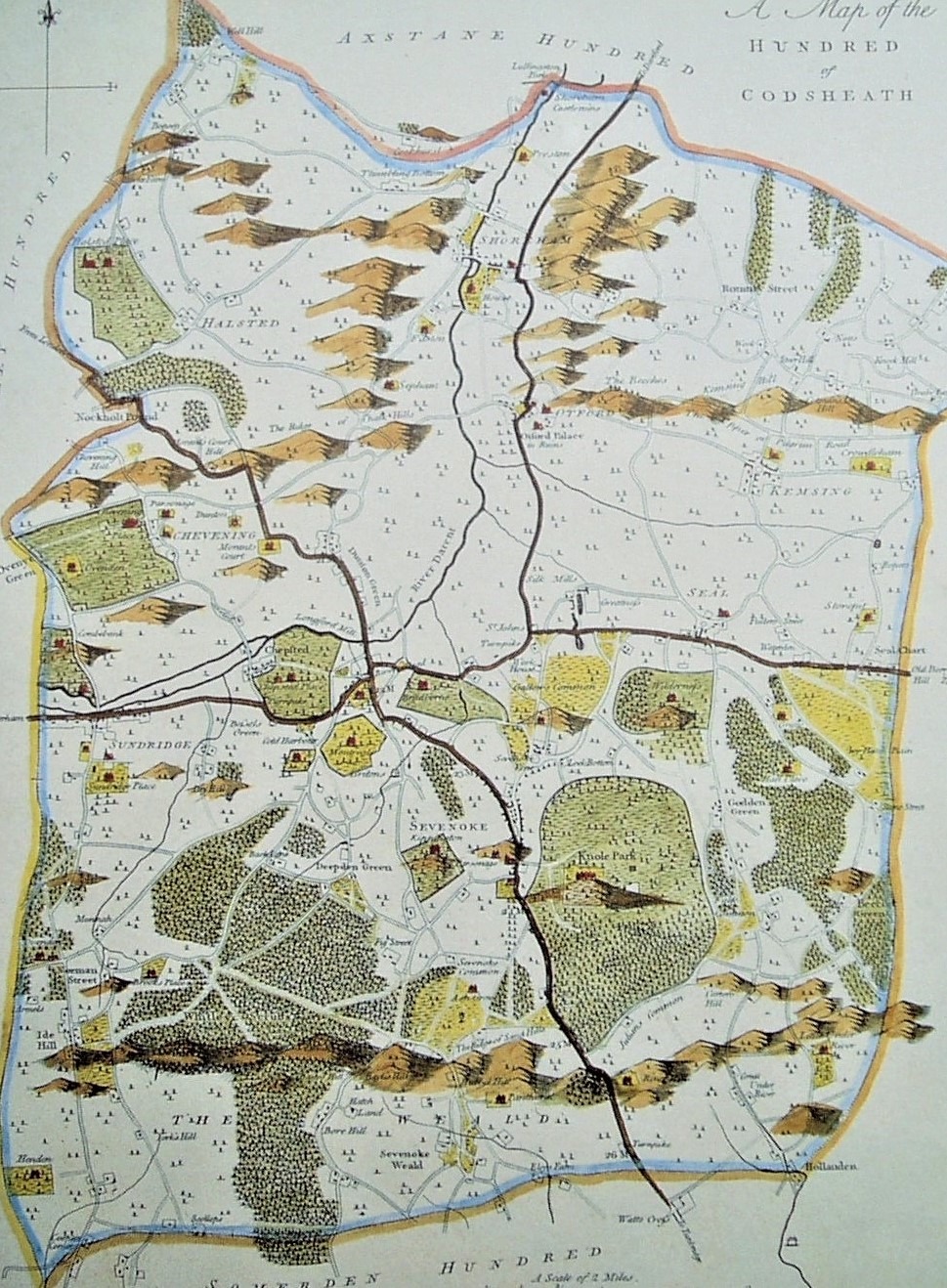

The landed gentry once dominated Sevenoaks. Many people worked in the mansion houses and surrounding grounds. Significant central Sevenoaks estates in the late 18th century were Knole, Montreal, Wildernesse, Kippington, Bradbourne and Greatness.

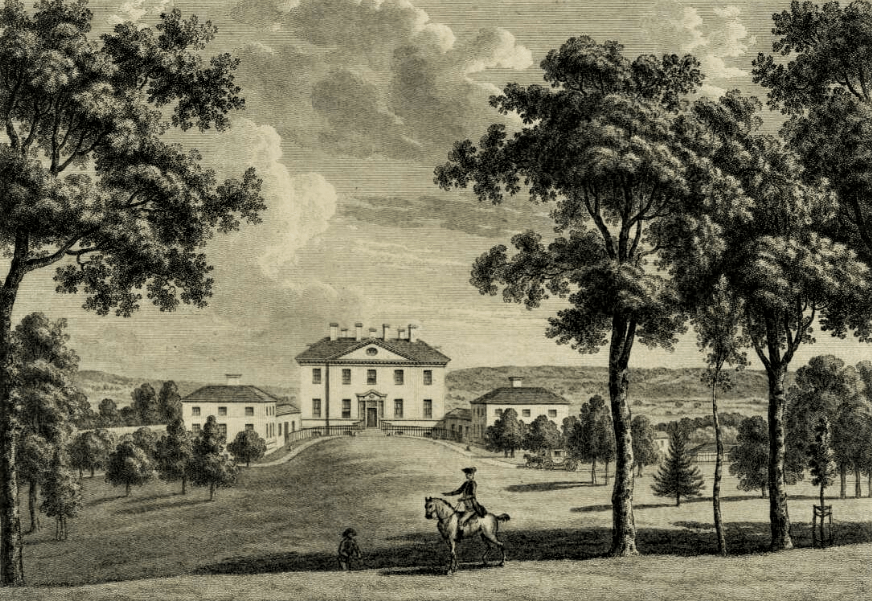

Montreal House was built for Jeffrey Amherst after his return from war in 1764, on an existing family estate. It had 27 bedrooms.

Commander in Chief of British Forces in North America when France surrendered Canada, Amherst was in many ways a hero to the local population. However, historical records tell of his particularly cruel disregard for the Native American population.

In 1926, Julius Runge purchased what was left of the Montreal estate to safeguard it from development. Of German Jewish heritage, Runge was the first Managing Director of the Tate and Lyle sugar company.

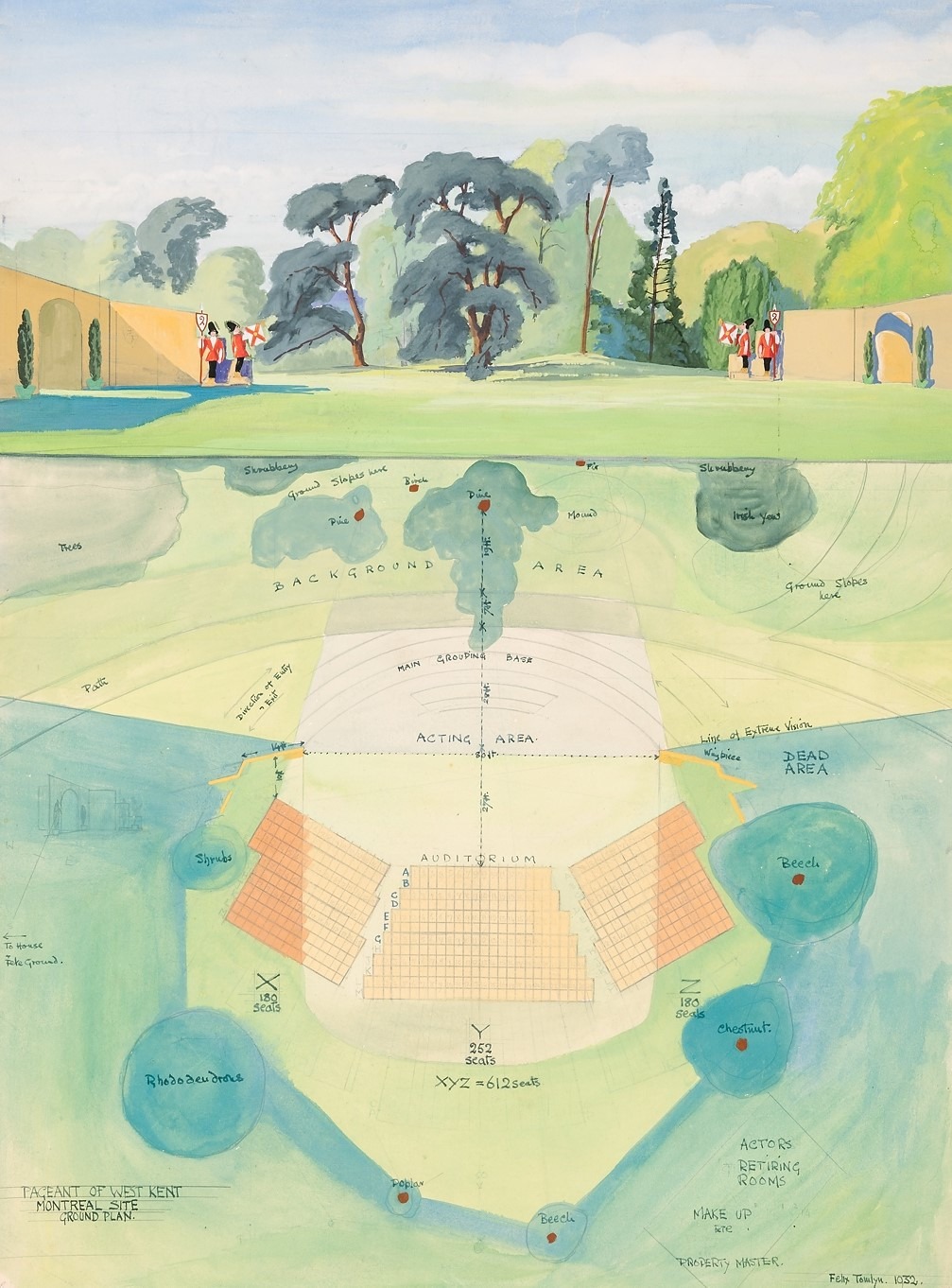

Montreal Park held the West Kent Pageant in 1932, an event involving 400 performers in dramatisations of historic events. In addition to the performance was a fair with refreshment stalls, side shows and games.

The Montreal estate was sold off after Runge’s death in 1935, mainly for housing. Today all that remains is a gatehouse, a derelict summerhouse and large obelisk.

Kippington House was built for politician Charles Farnaby in the late 1700s. Charles was a descendant of Thomas Farnaby, a Royalist who battled with Parliamentarian soldiers near Tonbridge in 1643.

Francis Motley Austen bought Kippington at the end of the 18th century. His uncle was William Austen, the novelist Jane Austen’s grandfather. In Jane Austen’s time the estate covered thousands of acres. During time spent with wealthy Sevenoaks relatives, she no doubt made some witty observations which informed her writing.

In the 19th century half of the Kippington land was bought by Lord Amherst to extend the Montreal estate. A strip of land was also sold for the railway to be built from London to Tonbridge in 1842.

Julius Runge lived at Kippington in 1926 and later bought and remodelled the house. As with Montreal, Kippington was sold after his death in 1935.

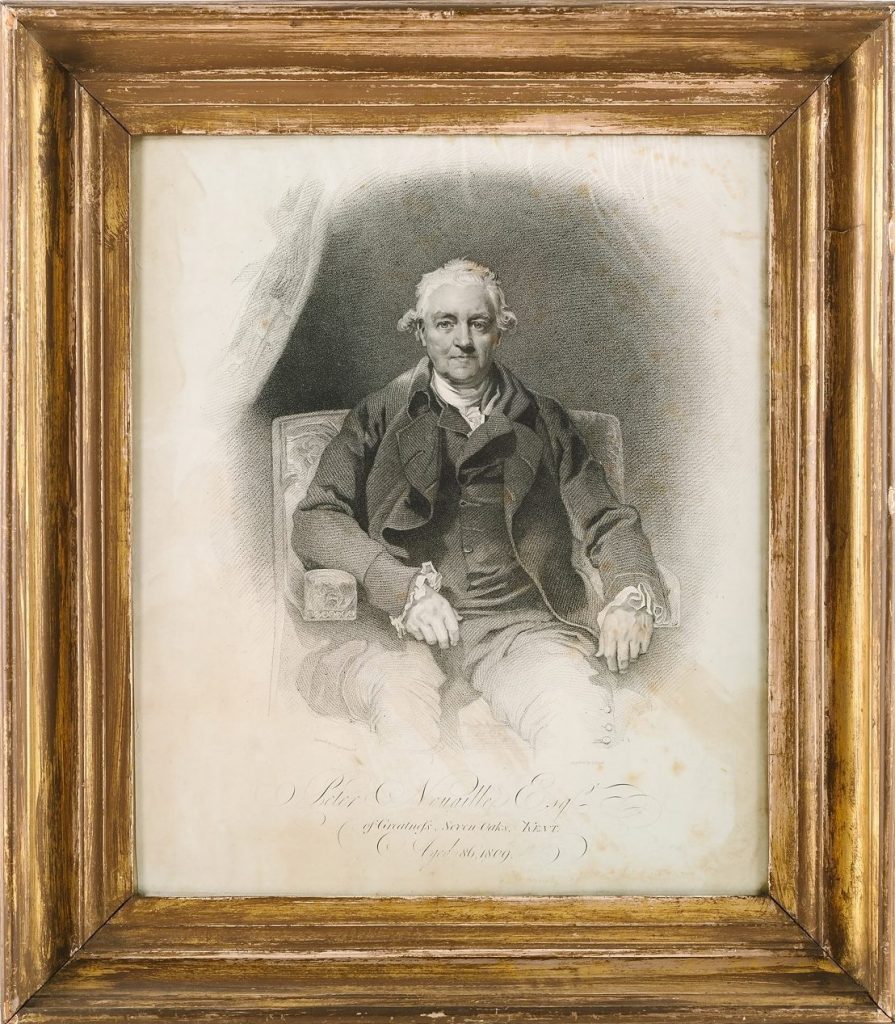

Greatness was home to the Nouaille family silk mill. The house was built in 1763 for Peter Nouaille, a Huguenot descendant. The Huguenots were French Protestants who fled persecution from the Catholic government in the 17th century. They played a significant role in the development of silk mills and the English textile industry, particularly in London’s Spitalfields district.

The silk factory was at peak production in 1766, when 100 people were employed, including children. It closed in 1828.

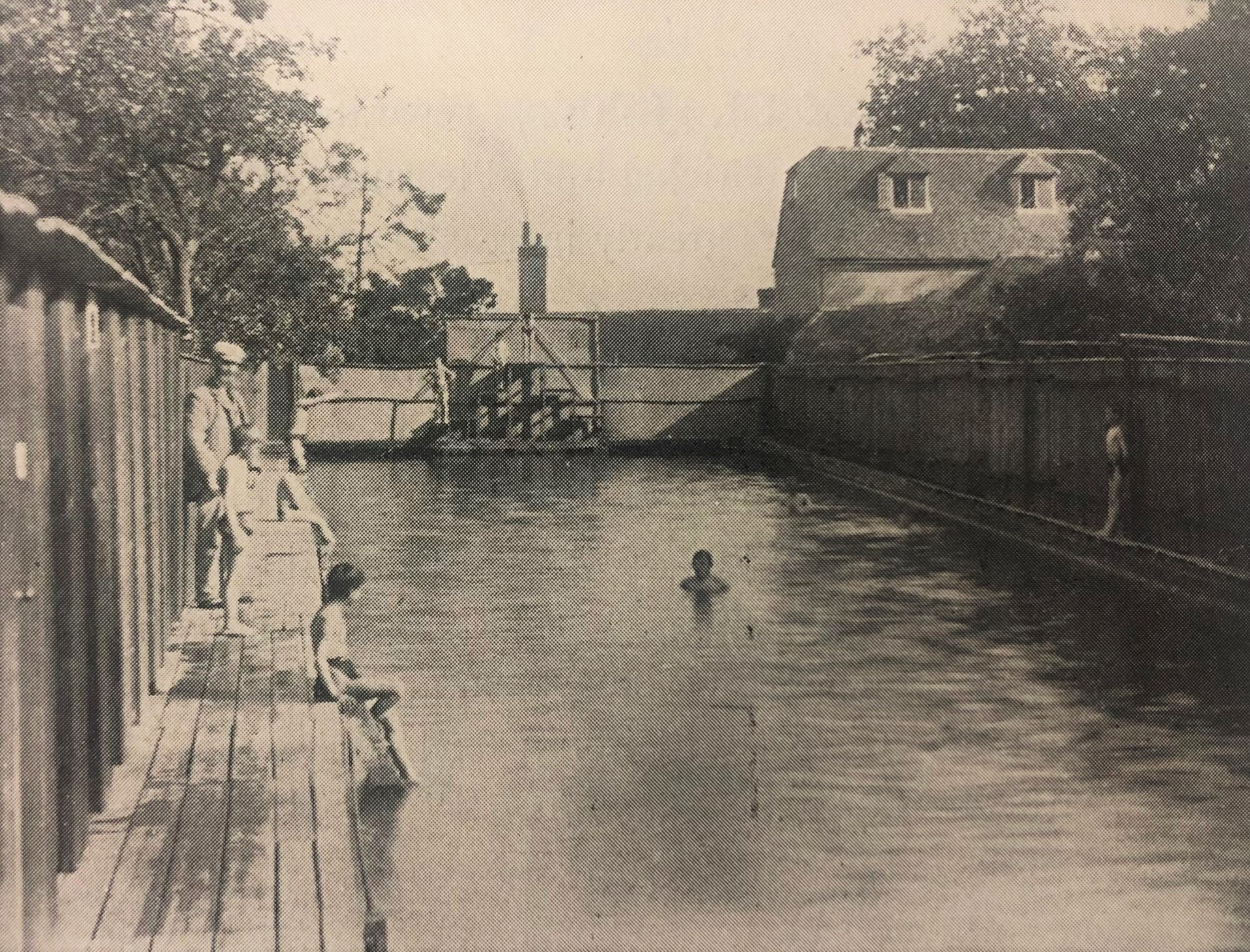

Railway engineer Thomas Crampton bought Greatness in 1864 and developed some of the land for industry. In the 1870s, one of the mill ponds was turned into an open air swimming pool.

In 1913, Sevenoaks Urban District Council bought the land to build the first council housing in the town. The house was eventually blown up in a dramatic explosion for a WW1 propaganda film.

The Wildernesse estate was huge and extended into both Seal and Sevenoaks. The first mansion was built in 1669, but it was extended by the Camden family who owned the estate from 1705 for 150 years. An avenue of lime trees was planted along the drive to celebrate a visit from the Duke of Wellington in 1815.

When the 2nd Marquis of Camden inherited the estate in 1840, he agreed to divide the land at Blackhall Farm which had been between the Wildernesse and Knole estates since the 12th century. The present Blackhall Lane marks the line of division.

In 1884, banker Charles Mills (later Lord Hillingdon) bought the estate. He was a great local benefactor and provided the land for Sevenoaks Hospital. Violet Mills managed the VAD hospital at Wildernesse during WW1 and was awarded an MBE for her service. The land was auctioned off in 1921, some for council housing and some for private development.

Bradbourne covered most of the northern part of Sevenoaks in the 16th century when it was owned by the Bosville family. It had its own chapel which later became the Clockhouse. Bradbourne lakes were originally part of the estate, laid out by Henry Bosville who owned Bradbourne until his death in 1761.

A notable resident of Bradbourne was the eccentric Welsh iron baron and millionaire Francis Crawshay, who bought the house in 1867 to live out his final years. Crawshay commissioned a large bell which he rang at six o’clock each morning and evening. He also erected druidic stone monuments in the grounds.

The house was demolished in 1937. After the land was divided up, the back garden of an ordinary terraced house ended up home to one Crawshay’s monoliths. Another can be found in the public park around the lakes.

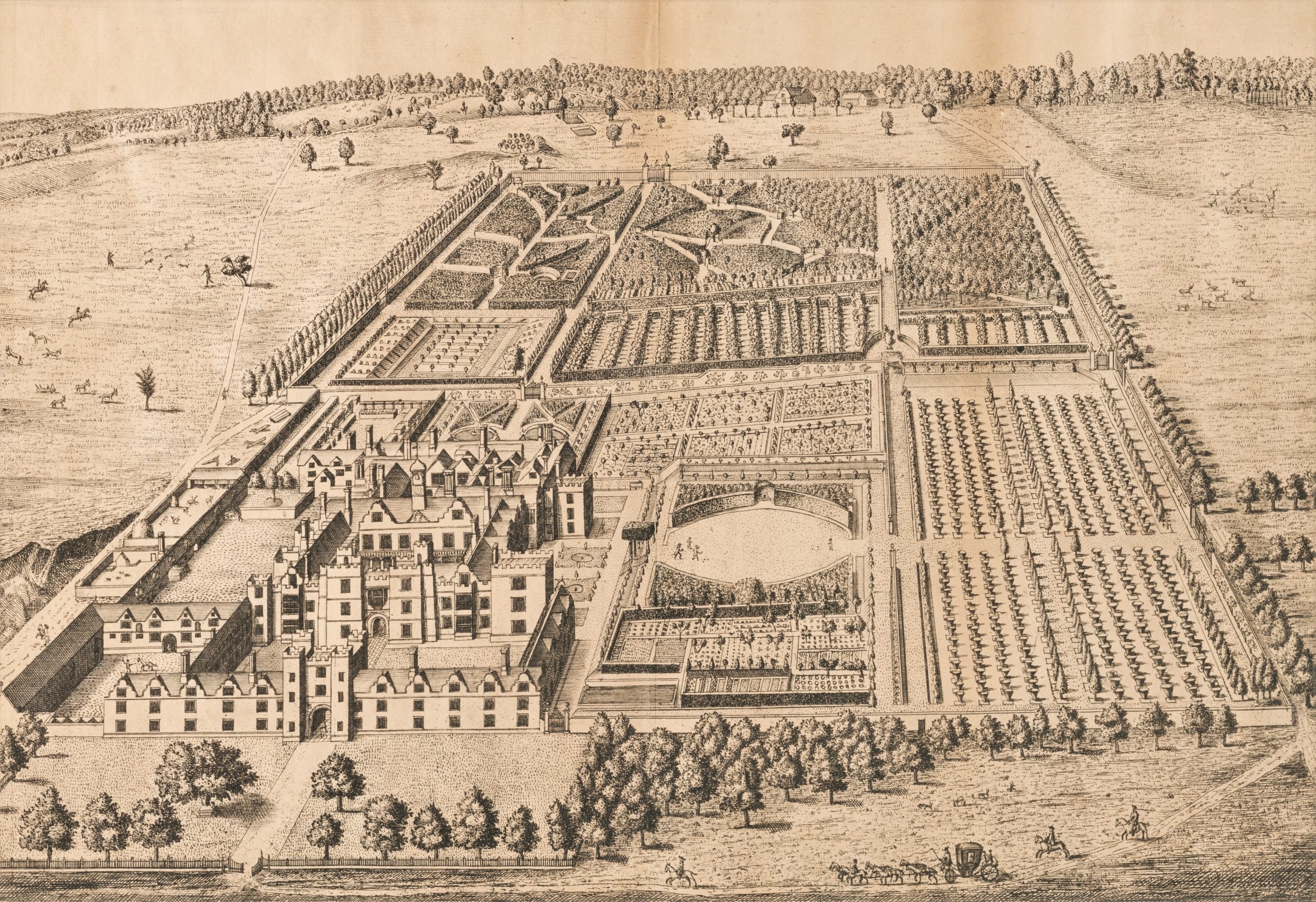

Knole’s transformation from a humble manor house into one of the grandest mansions in Kent began in 1456, when the property was bought by Archbishop Bourchier for £266. It was owned by successive archbishops until 1538, when King Henry VIII took Knole as a royal palace.

Thomas Sackville, 1st Earl of Dorset and cousin of Queen Elizabeth I, remodelled the house pretty much into what can be seen today, a vast mansion and aristocratic treasure trove. The Sackvilles and their descendants have lived at Knole from 1603 until the present day.

The earliest record of people of African heritage living in Sevenoaks is in the Knole inventory of house servants from 1613. Their names were John Morocco and Grace Robinson.

Lady Anne Clifford’s diary (available in the reference library) is a unique historical insight into the life of a Stuart noblewoman at Knole, detailing the frequent comings and goings of various dignitaries, as well as her difficult marriage to Richard Sackville, 3rd Earl of Dorset. It covers trivial household affairs as well as major events including the funeral of Queen Elizabeth I.

In 1642, during the Civil War, Knole House was raided by Oliver Cromwell’s troops. Weapons and armour in the house were seized.

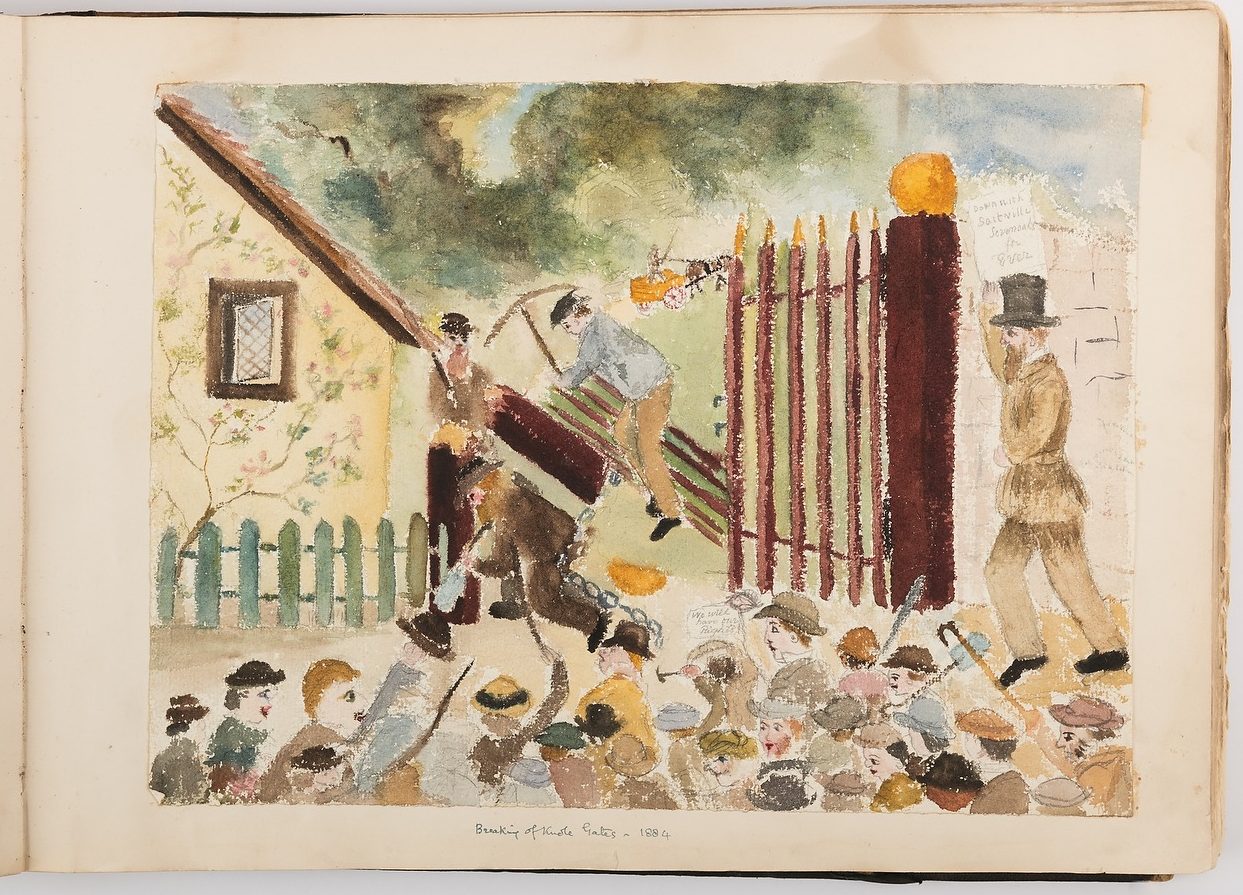

There was controversy in 1884 when the Lord Sackville, Mortimer Sackville-West, restricted public access through Knole Park. Riots ensued and a group of local people stormed the gates in protest. The ‘Guy’ paraded to the bonfire on 5 November was an effigy of Lord Sackville.

A major fire at Knole in 1887 damaged the medieval barn. Many townspeople attended the disaster. The barn now has a new roof and has been converted into a conservation studio to treat the historic Knole collection.

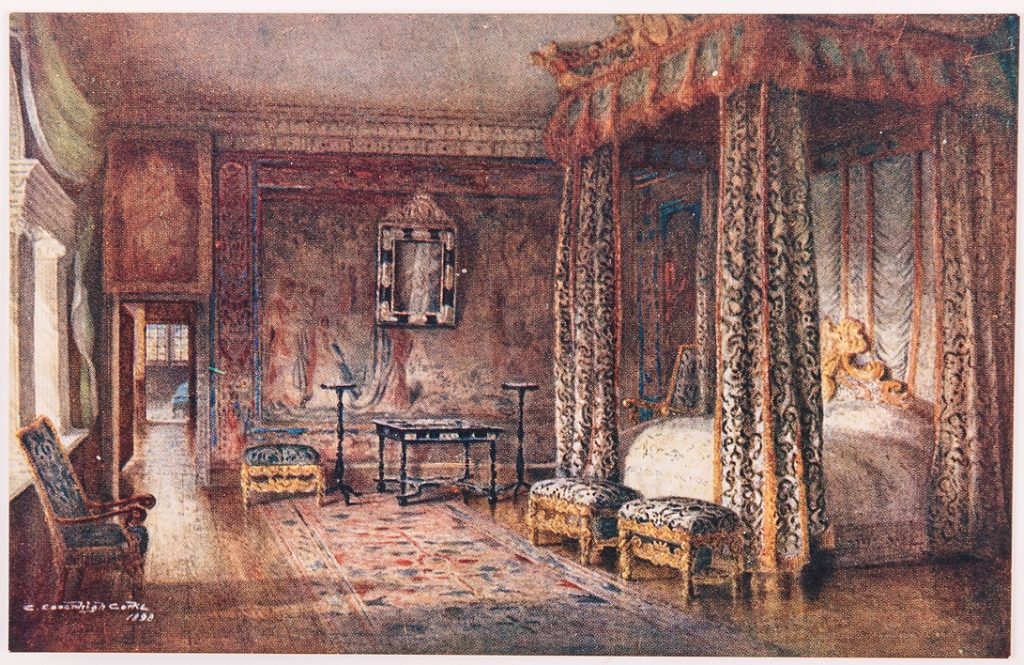

At the turn of the 20th century, Sevenoaks printers and publishers J. Salmon produced a series of illustrated colour postcards of Knole exteriors and interiors. They were reproductions of paintings by Charles Essenhigh Corke, local artist and photographer.

The Venetian Ambassador’s bedroom is described by Virginia Woolf in her 1928 novel, Orlando:

‘The room… shone like a shell that has lain at the bottom of the sea for centuries and has been crusted over and painted a million tints by the water…’

The book was inspired by Woolf’s intimate relationship with fellow writer Vita Sackville-West who grew up at Knole and was fascinated by its history. Vita was not an heir to the estate due to being a woman. The character Orlando is an Elizabethan nobleman who lives through 500 years and whose final reincarnation is female.

In 1967 the park was visited by some very famous musical guests when The Beatles filmed the video for the song Strawberry Fields Forever, featuring a distorted piano and some funny backwards walking around the trees.

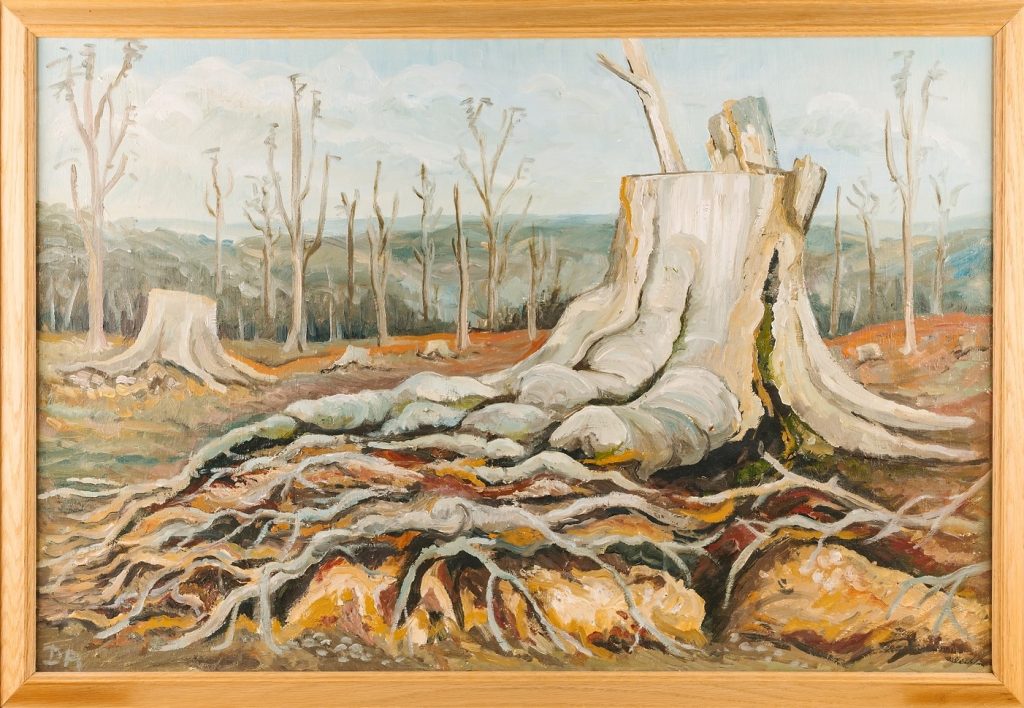

In the Great Storm of 1987, Knole lost over half of its trees. Many of the sweet chestnuts and other traditional trees were torn down by the extreme winds.

Knole was the only great estate in Sevenoaks not sold off piece by piece in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It still covers almost a thousand acres. Surrounding the house is the last surviving medieval deer park, inhabited by descendants of deer owned by Henry VIII.

Some objects from Knole House were donated to Sevenoaks Museum in the 1930s. In 1946, Knole was gifted to the National Trust to be opened to the public. The private apartments were leased back to the Sackville-West family who retain ownership of most of the parkland, the deer herd, and the contents of the house.

The museum holds other interesting objects relating to historic estates in the wider Sevenoaks area…

This leather bound box was used for holding Wickhurst manorial records in the 1600s. Wickhurst Manor included a large house and farmland, dating back to Medieval times. In 1611 it had 160 acres.

A surviving document from 1642 states that Wickhurst rents were to be received ‘on St. Andrew’s Day at sunrising at a maple tree standing in Leigh parish in Kent near the highway leading from Sevenoaks to Penshurst.’ The rent collector is named as Thomas Medhurst, who has been given ‘a horn to summon in the tenants with, according to the customs of the said manor’.

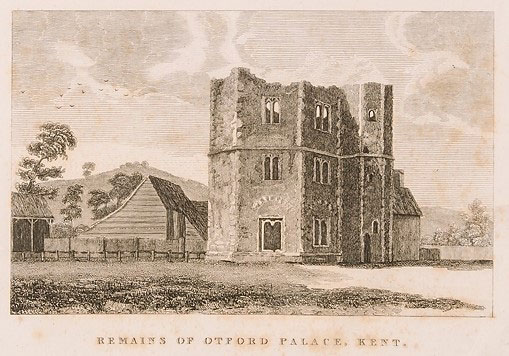

We know from the Domesday book of 1086 that Otford was the largest manor in the area, covering 20 square miles. Encompassing modern Sevenoaks, it was in the largest 20% of settlements in the whole country. In 1515, Archbishop Warham built a grand palace, replacing the older manor house. A short lived extravagance, the palace fell into disrepair in the 1600s.

Tiles were made from clay, pressed into moulds, and the surplus cut off with wire. They were left to dry until hard, then trimmed, glazed and fired. Medieval glazes were based on scrap lead which was heated in a furnace until it turned into oxide powder. This was brushed on to the tile surface before firing.

Bicoloured tiles were introduced from the late Medieval period. A carved wooden stamp would be pressed into the tile, and the cavities filled with white clay, before glazing and firing. This style was revived in the Victorian period.

Written by Liz Botterill, Curator